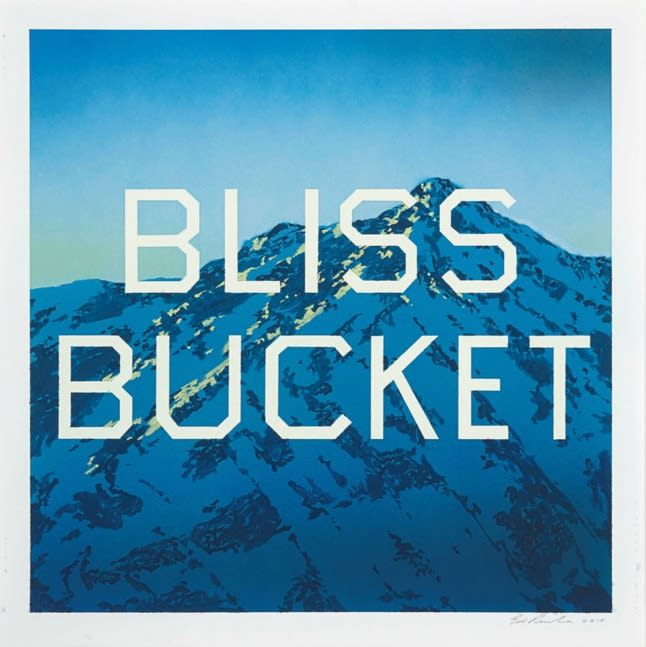

Ed Ruscha b. 1937

Bliss Bucket, 2010

Acrylic on paper

28 x 28 inches

71.1 x 71.1 cm

71.1 x 71.1 cm

Signed and dated lower right recto

Sold

Juxtaposed with a strikingly blue mountain peak, Bliss Bucket is set boldly in the center of the frame, creating a fusion of text and landscape intrinsic within Ruscha's most iconic...

Juxtaposed with a strikingly blue mountain peak, Bliss Bucket is set boldly in the center of the frame, creating a fusion of text and landscape intrinsic within Ruscha's most iconic works. The bright white lettering captures the eye, highlighting the small pockets of sunshine catching the mountain's snowy top. Executed in 2010, Bliss Bucket resembles the acclaimed Mountain Pictures series Ruscha began in the late 1990s, examples of which have been included in museum collections such as Tate Modern, London.

Rendered hyper realistically using a 'paint-by-numbers' technique, the shadowed snowy mountain creates an ombré effect of magnificent cool blues. The stark white text leaps from the darkness of the peak leading the eye from the light sky down through the bowls of the mountain. Situated directly below the wind ridden summit, consuming the majority of the frame, the text reveals Ruscha's optical genius creating a necessary tension between text and image.

The crisp lettering emphasizes the sharp articulation of the landscape behind it. Having trained as a sign painter, this attention to typography reveals Ruscha's passion for words. A relationship which has become very intimate: 'Words have temperatures to me. When they have reached a certain point and become hot words they appeal to me... sometimes I have a dream that if a word gets too hot and too appealing, it will boil apart, and I won't be able to read or think of it' (E. Ruscha, 'Repainting, redrawing and rephotographing Los Angeles', Art Newspaper, published online: 19 December 2012.)

Influenced by the brilliant and provocative surrealist, René Magritte, words for Ruscha clearly have an evocative and playful nature. Magritte illuminated paradoxes between text and image causing the viewer to question the relationship presented. The Treachery of Images, 1928-29, is where Magritte so aptly expressed that a painting of a pipe is not in fact a pipe. Rushca pushes this idea further by producing hyper realistic images; Bliss Bucket is so obsessively and meticulously rendered it appears to be a photograph. Furthermore, the large all encompassing text indicates itself as a title, a subject, and caption, obscuring the meaning altogether. Visual and verbal means of communication coexist to create this sense of dislocation.

Through numerous layers of association it is clear Ruscha enjoys conceiving of a dislocation for his viewer: 'Usually in my paintings, I'm creating some sort of disorder between the different elements', Ruscha has said 'and avoiding the recognizable aspect of living things by painting words. I like the feeling of an enormous pressure in a painting' (E. Ruscha, quoted in R. Marshall, Ed Ruscha, New York 2003, p. 241).

Rendered hyper realistically using a 'paint-by-numbers' technique, the shadowed snowy mountain creates an ombré effect of magnificent cool blues. The stark white text leaps from the darkness of the peak leading the eye from the light sky down through the bowls of the mountain. Situated directly below the wind ridden summit, consuming the majority of the frame, the text reveals Ruscha's optical genius creating a necessary tension between text and image.

The crisp lettering emphasizes the sharp articulation of the landscape behind it. Having trained as a sign painter, this attention to typography reveals Ruscha's passion for words. A relationship which has become very intimate: 'Words have temperatures to me. When they have reached a certain point and become hot words they appeal to me... sometimes I have a dream that if a word gets too hot and too appealing, it will boil apart, and I won't be able to read or think of it' (E. Ruscha, 'Repainting, redrawing and rephotographing Los Angeles', Art Newspaper, published online: 19 December 2012.)

Influenced by the brilliant and provocative surrealist, René Magritte, words for Ruscha clearly have an evocative and playful nature. Magritte illuminated paradoxes between text and image causing the viewer to question the relationship presented. The Treachery of Images, 1928-29, is where Magritte so aptly expressed that a painting of a pipe is not in fact a pipe. Rushca pushes this idea further by producing hyper realistic images; Bliss Bucket is so obsessively and meticulously rendered it appears to be a photograph. Furthermore, the large all encompassing text indicates itself as a title, a subject, and caption, obscuring the meaning altogether. Visual and verbal means of communication coexist to create this sense of dislocation.

Through numerous layers of association it is clear Ruscha enjoys conceiving of a dislocation for his viewer: 'Usually in my paintings, I'm creating some sort of disorder between the different elements', Ruscha has said 'and avoiding the recognizable aspect of living things by painting words. I like the feeling of an enormous pressure in a painting' (E. Ruscha, quoted in R. Marshall, Ed Ruscha, New York 2003, p. 241).